The Terrible Noises Outside

History Doesn’t Repeat. It Rhymes in Real Time.

February in New Jersey is a color more than a month. It’s the shade of wet concrete and exhausted sky, sidewalks crusted with old salt, lawns still pressed flat beneath winter’s palm. Snowbanks slump along the curb, hardened and ridged, worn down by days that warmed just enough to melt and then refroze overnight. The air carries that metallic chill that slips through coat sleeves and settles into your knuckles. Even the light feels tired, like it woke up but never fully stood.

At 7:18 a.m., the school bus stop is a constellation of puffed jackets and knit hats and backpacks too large for the spines carrying them. Snow underfoot is compacted and slick, gritty with sand, treacherous in that quiet way February specializes in. Every exhale leaves a small white cloud that blooms and disappears, blooms and disappears — proof these children are warm inside even if everything around them is cold.

They shuffle in place, sneakers grinding against ice, that restless bounce kids do when they’re trying to keep circulation in their toes. One boy is replaying math homework in his head. Another is blinking through the last grains of sleep. Two girls whisper about Roblox and lip stain. They’re worried about quizzes and recess and whether the cafeteria will run out of chocolate milk.

It is small. Ordinary. Tender in its normalcy.

And then someone says it.

ICE.

The word moves through them faster than comprehension. It hits the bloodstream and the body decides.

Backpacks swing. Breath catches. A scream slices the gray air and then there are ten more. Children scatter across the parking lot and between buildings, sneakers slipping on refrozen snow, hands grabbing at straps, at sleeves, at nothing. Ponytails whip. A mitten drops and is abandoned. The geometry of a bus stop dissolves into survival.

Run.

There’s a Ring camera that catches a ten-year-old boy at his own front door, fists hammering wood with a rhythm that isn’t knocking, it’s pleading. His whole small body is pitched forward as if he could will the lock to turn faster, breath fogging the lens in frantic bursts.

Open the door!

Open the door!!

ICE!!

I keep seeing those clouds of breath at the bus stop — how moments earlier they drifted upward in gossip and laughter, and how quickly they became exhaust. Nothing about the sky changed. Nothing about the snow shifted. Only their sense of safety did.

And I can’t stop thinking about what had to already be living inside them for that word to trigger flight.

You don’t run like that unless terror has already taken up residence. You don’t scream like that unless the possibility has already been sitting at the kitchen table with you before breakfast.

Whole communities are living inside that readiness now. Curtains half-drawn. Phones clutched. Conversations clipped short when a car slows at the end of the block. These kids have seen fathers taken between pickup and dinner. Mothers pulled from parking lots. Classmates gone from desks that were still warm. They’ve watched children swept up in the same dragnet, backpacks still on their shoulders.

So when someone says ICE, it bypasses thought entirely.

Last summer a hurricane tore through our town without warning. The sky went green and branches cartwheeled through sideways rain. I was driving home and every block closer to my house tightened something in my chest because my kids were home and I was not. I remember pounding on my front door, fists striking wood, desperate to get inside and drag my children to the basement.

I was pounding on that door to get to my children, to drag them down to the basement and shield them from a storm.

That young boy was pounding on his door to get to his mother, to shield himself from us.

And while ten-year-olds are learning how to run from our government, children as young as two months old are sleeping behind fencing in concentration camps run by it. Toddlers warehoused under institutional light. Kids carving their own skin to survive the hours. A five-year-old in a floppy-eared hat released by court order — and this administration fought to put him back in that same camp.

They fought to put him back.

Republicans call themselves protectors of children. They say they are pro-life. They build entire campaigns around invented threats to innocence while children sit on concrete floors in concentration camps with aluminum blankets crinkling under fluorescent glare.

After all the rhetoric, after all the reverent language, after all the manufactured panic, the simple truth is this — Republicans don’t give a fuck about children. All they care about is control. All they care about is power.

Fear works for them. Division keeps the machine humming. Dehumanization makes the rest of it possible.

Pam Bondi is the face of that metastasized rot.

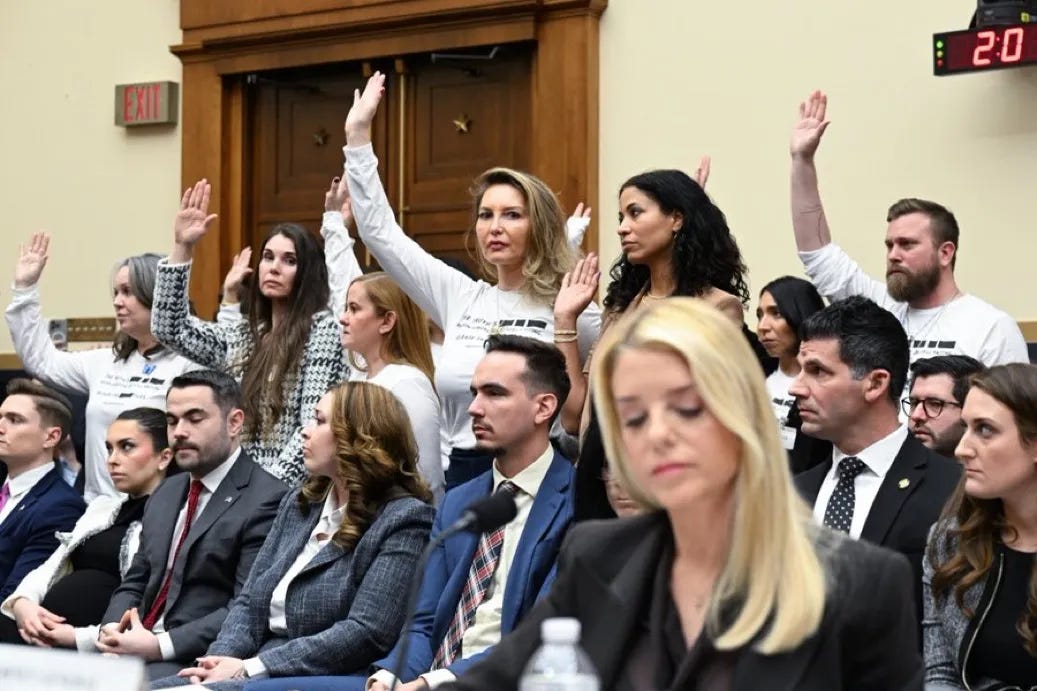

That photograph — her seated at that long polished table, survivors standing behind her with entire girlhoods folded into their shoulders — holds more truth than any transcript. Those women carried memory in their bones. Bondi carried a smirk.

I know that face well.

When I was four years old, I was sitting in my mother’s closet on a pile of her fancy shoes, playing with my favorite pair. They were gold and strappy and I thought they were the prettiest things in all the world.

The closet door swung open.

She stood above me and ripped the shoe out of my hand, and before I understood what was happening she drove the heel into my face. I remember the metallic taste of blood flooding my mouth. I remember my hands coming up, small and useless, trying to hold my own face together while it poured through my fingers.

And I remember looking up at her.

Waiting.

Waiting for horror. Waiting for panic. Waiting for some flicker that said I mattered more than the shoes.

Her face was almost snarling. She didn’t care that she had permanently scarred me. She didn’t care that I was bleeding. She didn’t care that I was scared. She had that same smug smirk.

I have a scar on the outside. I’m pretty sure I’m the only one who notices it much anymore. But that day broke something in me — something I’ve worked my entire life to heal.

It rewired something in me. I learned to read a face while I was bleeding. I learned how easily someone can stand over damage and remain untouched by it. I learned how cruelty can echo louder than a scream.

It’s a lesson I’ve had to learn over and over again, I’m afraid.

So when I look at Pam Bondi in that photograph, I feel four years old again for a split second. Small. Hurt. Waiting for something that isn’t coming.

And my stomach drops in a way I know too well.

Because I have lived inside that kind of heartlessness.

And I know what it costs the child.

And I think that’s why lately, everywhere I go, I find myself scanning faces.

Are they able to look at this and shrug?

Are they able to look at this and say, “that’s what I voted for”?

Are they able to look at this and feel disturbed — and then simply look away?

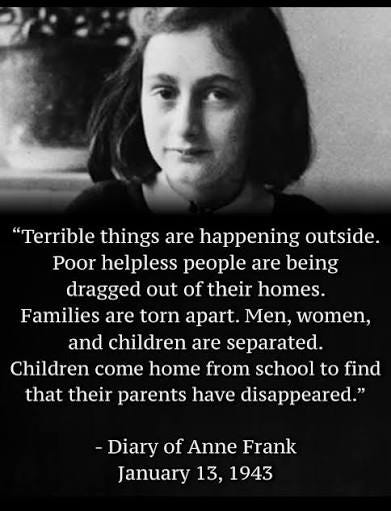

When I was thirteen, sitting in Mrs. Callahan’s classroom reading The Diary of Anne Frank, there was a single question I could not let go.

What did the “good Germans” do?

How did they look away?

How did they let it happen?

How did they go home and sit at their tables while terrible noises were happening outside?

I remember believing I was studying something sealed in history — the worst already endured, catalogued, sworn over in museums and textbooks never to be repeated. I naïvely believed it was behind us.

I never imagined I would grow up and feel its rhythms echoing anywhere near my backyard.

Anne Frank wrote:

“Terrible things are happening outside… Families are torn apart; men, women and children are separated. Children come home from school to find that their parents have disappeared.”

Those words were written in another country, under another flag, in a different time.

But they now feel dangerously fluent in ours.

Somewhere in America right now, a little girl is hiding in an attic and she’s writing about what I.C.E. is doing outside. Somewhere a child is listening for engines idling. Somewhere a kid is walking home from school bracing for absence.

Genocide does not materialize in a single day. It accumulates quietly — in the words we tolerate, in the laws we excuse, in the moments we tell ourselves it isn’t our place to intervene while terrible noises are happening outside.

When I used to ask what the “good Germans” did, I didn’t know I would one day have the answer.

The people who can watch children scatter from our own government and shrug are the answer.

As a mother. As a human being. As part of this fierce and beautiful community of ours. I sure as shit refuse to be counted among them.

And with that, today’s song:

I love you guys!

Stay strong, please stay safe, and stay connected to one another.

💙 Jo

JoJo

I’m so sorry your mum was so bad to you.. genuinely upset

But I see in your words and actions that YOU have a depth to your soul. Love in your heart and a mothers love for HER FAMILY 🌟❤️🙏

You inspire me to be a better person

Powerful words and images JoJo. When is this nightmare going to end, and why aren’t right wingers and republicans freaking out? Reminds me of the book “Hitler’s Willing Executioners.” As someone who spent my first years as an educator teaching kindergartners and first graders, this just makes my heart and soul weep.